How Antidepressants Help Treat Functional Dyspepsia

Oct, 16 2025

Oct, 16 2025

Functional Dyspepsia Antidepressant Selector

Personalized Recommendation Tool

Select your primary symptoms and concerns to get evidence-based guidance on which antidepressant class may be most appropriate for your functional dyspepsia.

Recommended Option

Why this recommendation?

Quick Takeaways

- Functional dyspepsia affects up to 20% of adults and often resists standard acid‑suppressive therapy.

- Antidepressants work by modulating the gut‑brain axis, not just by treating mood disorders.

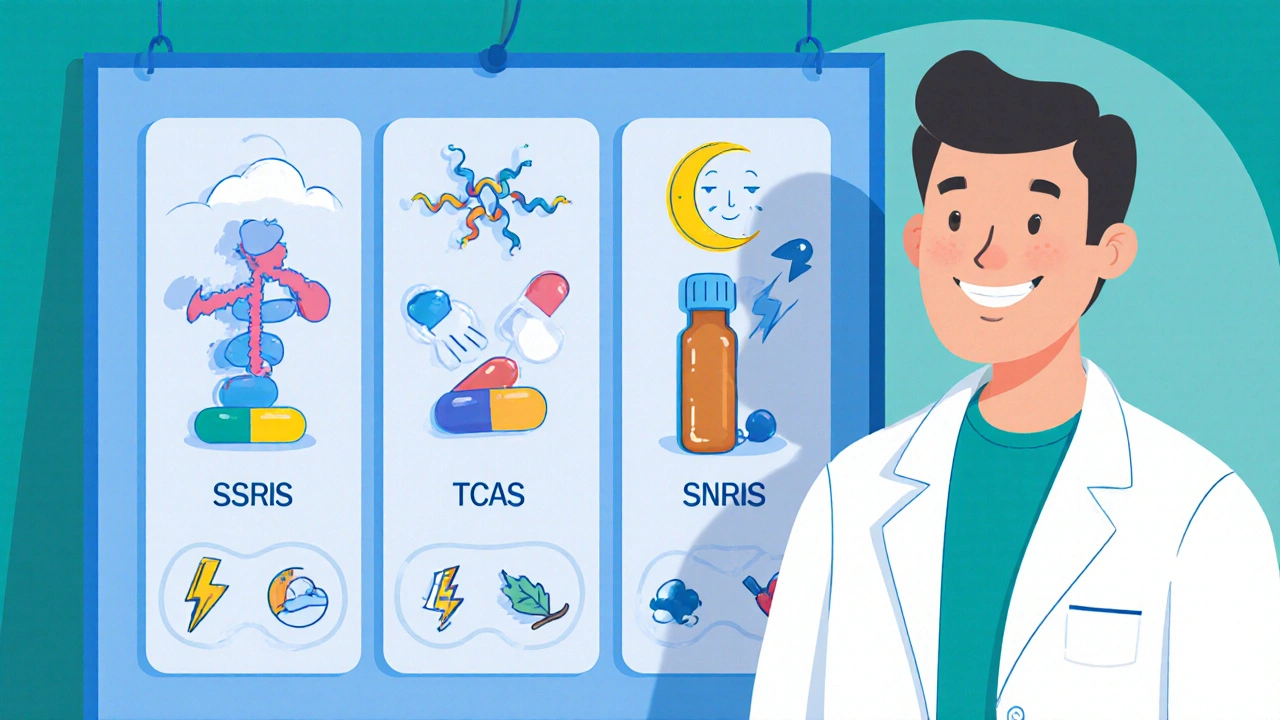

- SSRIs, TCAs, and SNRIs each have a different safety and efficacy profile for dyspepsia.

- Choosing the right class depends on symptom pattern, comorbid anxiety/depression, and side‑effect tolerance.

- Start low, go slow, and reassess after 6‑8 weeks to gauge benefit.

When doctors talk about Functional Dyspepsia is a chronic upper‑GI disorder characterized by post‑prandial fullness, early satiety, and epigastric pain without an obvious structural cause. The Rome IV criteria define it based on symptom duration of at least three months and exclusion of organic disease.

In recent years, Antidepressants have emerged as a therapeutic option-not because patients are necessarily depressed, but because many of these drugs influence the gut‑brain axis, a two‑way communication line between the central nervous system and the enteric nervous system. This axis involves neurotransmitters such as serotonin and norepinephrine, which regulate motility, visceral sensitivity, and inflammation.

Three major antidepressant families are most studied for dyspepsia:

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) boost synaptic serotonin, which can improve gastric accommodation and reduce pain perception.

- Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) block reuptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine and have anticholinergic effects that slow gut transit, helpful for patients with diarrhea‑dominant symptoms.

- Serotonin‑Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) combine the benefits of SSRIs and TCAs with a more favorable side‑effect profile.

Why Antidepressants Work in Functional Dyspepsia

The gut houses about 95% of the body’s serotonin. When an antidepressant modifies serotonin signaling, it directly influences gut motility and sensitivity. Moreover, many patients with functional dyspepsia report comorbid anxiety or low‑grade depression, which can amplify pain through central sensitization. By dampening this central amplification, antidepressants break the vicious cycle of stress‑induced gut discomfort.

Clinical trials from 2018‑2024 consistently show modest but statistically significant symptom relief compared with placebo. A 2022 meta‑analysis of 14 randomized controlled trials reported a pooled odds ratio of 1.45 for symptom improvement when using any antidepressant, with the strongest effect seen for TCAs (OR=1.62).

Choosing the Right Antidepressant Class

| Class | Typical Dose for Dyspepsia | Evidence Strength | Common Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSRIs (e.g., escitalopram) | 5‑10mg daily | Moderate (12 RCTs) | Nausea, insomnia, sexual dysfunction |

| TCAs (e.g., amitriptyline) | 10‑25mg at bedtime | Strong (8 RCTs) | Dry mouth, constipation, drowsiness |

| SNRIs (e.g., venlafaxine) | 37.5‑75mg daily | Emerging (5 RCTs) | Hypertension, headache, sweating |

For patients whose dominant complaint is early satiety and post‑prandial pain, low‑dose TCAs are often first‑line because the anticholinergic effect slows gastric emptying, giving the stomach more time to accommodate food. If constipation is already an issue, an SSRI or SNRI may be preferable.

Practical Initiation and Titration

- Confirm the diagnosis of functional dyspepsia using the Rome IV criteria and rule out H. pylori, peptic ulcer disease, and malignancy with endoscopy if indicated.

- Assess comorbid anxiety or depression using a brief tool such as the GAD‑7 or PHQ‑9. This informs drug choice.

- Start with the lowest effective dose: e.g., amitriptyline 10mg at night or escitalopram 5mg in the morning.

- Schedule follow‑up at 4 weeks to check tolerability; increase dose by 10‑25mg increments if side effects are minimal.

- Re‑evaluate symptom scores (e.g., Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire) after 6‑8 weeks. Continue therapy if there is ≥30% improvement.

- If no benefit after 12 weeks, consider switching class or adding a prokinetic such as itopride.

Because many patients experience a “placebo effect” with any new medication, a blinded trial run‑in (e.g., 2 weeks) can help differentiate true pharmacologic benefit.

When Antidepressants Might Not Be Appropriate

Even though antidepressants are generally safe, certain scenarios call for caution:

- Severe cardiac disease: TCAs can prolong QT interval.

- Pregnancy or lactation: Data on SSRIs and SNRIs are mixed; discuss risks with OB‑GYN.

- Concurrent MAOI therapy: Risk of serotonin syndrome.

- History of bipolar disorder: Antidepressants can trigger mania.

In these cases, focusing on dietary modification, low‑dose proton pump inhibitors, or behavioral therapies (e.g., gut‑focused CBT) may be wiser.

Integrating Lifestyle and Behavioral Strategies

Antidepressants work best as part of a multimodal plan. Evidence shows that antidepressants for functional dyspepsia combined with a low‑FODMAP diet reduces symptom scores more than either approach alone. Mindfulness‑based stress reduction (MBSR) and hypnotherapy have also shown modest gains, likely by dampening central pain amplification.

Key lifestyle tips:

- Eat smaller, more frequent meals to avoid overstretching the stomach.

- Avoid trigger foods such as fatty meals, caffeine, and alcohol.

- Maintain a regular sleep schedule; poor sleep worsens visceral hypersensitivity.

- Engage in moderate aerobic exercise (30min most days) to improve gut motility.

Monitoring and Long‑Term Management

After establishing benefit, most clinicians keep patients on the lowest effective dose for at least six months before considering taper. Sudden discontinuation can cause withdrawal symptoms-often described as “brain zaps” or rebound GI discomfort.

Routine labs (CBC, LFTs) are usually not required unless the patient has hepatic disease. However, a yearly review of mental health status is prudent, especially if the initial indication was subclinical anxiety.

Future Directions

Research is moving toward personalized therapy. Genetic testing for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 polymorphisms may predict TCA metabolism speed, while gut microbiome profiling could identify patients who will respond best to serotonergic agents.

Emerging agents like the 5‑HT4 agonist prucalopride and the neuropathic pain modulator duloxetine are in phase‑III trials, hinting at a future where targeted gut‑brain drugs replace broad‑spectrum antidepressants.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can antidepressants cure functional dyspepsia?

They rarely cure the condition outright, but they can significantly reduce symptoms for many patients, especially when combined with diet and behavioral changes.

How long does it take to see improvement?

Most studies report noticeable relief after 4‑6 weeks of consistent dosing, though full benefit may take up to 12 weeks.

Are there risks of dependence?

Physical dependence is uncommon; however, abrupt stopping can cause withdrawal symptoms, so tapering is recommended.

Do I need a prescription for these drugs?

Yes, all SSRIs, TCAs, and SNRIs require a doctor’s prescription in the United States and most other countries.

What if I have both constipation and reflux?

A low‑dose TCA can help with reflux‑type symptoms but may worsen constipation; in such mixed cases, an SSRI combined with a prokinetic is often the better balance.

Rex Wang

October 16, 2025 AT 15:56The gut‑brain axis isn’t a buzzword; it’s a real bidirectional pathway that can be modulated by low‑dose antidepressants.

Jessica Taranto

October 21, 2025 AT 07:03I’ve tried a low‑dose amitriptyline for a few months and noticed that my post‑meal fullness decreased noticeably. Starting at 10 mg at bedtime gave me a gentle anticholinergic effect without the classic drowsy crash. It helped me space my meals more comfortably and reduced the early satiety that used to limit my diet. Of course, I monitored my mood and bowel habits closely, adjusting the dose only if side effects emerged.

akash chaudhary

October 25, 2025 AT 22:10This write‑up glosses over the fact that tricyclics can prolong the QT interval and precipitate arrhythmias, especially in patients with underlying cardiac disease. It also ignores the risk of anticholinergic delirium in older adults, which can be catastrophic. The “start low, go slow” advice is naive when the drug class carries such lethal potential. A more responsible article would flag these dangers prominently.

Adele Joablife

October 30, 2025 AT 12:16While the evidence does suggest modest benefit from serotonergic agents, we must remember that “modest” often translates to “clinically insignificant” for many patients. The side‑effect profiles differ, and the decision should weigh personal tolerance over generic trial data. In practice, I find that a trial of an SSRI works best for those already dealing with anxiety, whereas TCAs suit patients with constipation‑dominant dyspepsia. Ultimately, shared decision‑making is key.

kenneth strachan

November 4, 2025 AT 03:23Yo, this stuff is kinda wild! Who knew a “mood pill” could chill your gut? I started on escitalopram 5 mg and felt less bloated after a couple weeks – like my stomach finally got the memo to relax. Yeah, I missed a dose once and felt a weird jitter, but nothing crazy. If you’re scared of the weird drug names, just ask your doc for the cheap generic and give it a shot.

Mandy Mehalko

November 8, 2025 AT 18:30Hey guys! I’m super happy you’re talking about diet + meds – it’s like a team sport for the belly! I tried adding a low‑FODMAP plan while on a tiny dose of venlafaxine, and wow, the burps stopped. I did mess up a typo in my log (writen vs written), lol, but the progress kept me excited. Keep the positive vibes rolling, and remember small wins add up!

Bryan Kopp

November 13, 2025 AT 09:36I’ve been on a low‑dose TCA for six weeks with mixed results; the constipation got worse before it got better. It’s a reminder that not every gut‑brain drug works the same way for everyone. Patience is a virtue, but also keep an eye on any new symptoms.

Patrick Vande Ven

November 18, 2025 AT 00:43From a pharmacological standpoint, the differential affinity of SSRIs for the 5‑HT₄ receptor may underlie their pro‑kinetic effects, whereas TCAs exert anticholinergic activity that can slow gastric emptying. The therapeutic window is narrow; therefore, titration schedules should be individualized based on the patient’s comorbidities and baseline motility pattern. Moreover, clinicians ought to consider cytochrome P450 polymorphisms when prescribing, as these can significantly affect plasma concentrations.

Tim Giles

November 22, 2025 AT 15:50In reviewing the literature, one observes that the heterogeneity of functional dyspepsia phenotypes necessitates a stratified therapeutic approach, wherein symptom clusters such as epigastric pain‑predominant versus post‑prandial distress‑dominant presentations guide the selection of antidepressant class. For instance, low‑dose amitriptyline, with its anticholinergic properties, may confer benefit in patients whose primary complaint is early satiety, whereas SSRIs could be preferentially employed in individuals exhibiting comorbid anxiety or heightened visceral hypersensitivity. Nonetheless, the placebo response in gastrointestinal trials remains substantial, often exceeding 30%, thereby complicating the interpretation of efficacy signals. Consequently, a double‑blind run‑in phase, as suggested, can serve to delineate true pharmacodynamic benefit. Additionally, emerging data on gut microbiota modulation by serotonergic agents hint at an ancillary mechanism that may augment symptom relief, a topic worthy of further investigation.

Peter Jones

November 27, 2025 AT 06:56I think the takeaway is that antidepressants are just one piece of the puzzle. Combining them with lifestyle tweaks, like smaller meals and regular exercise, seems to give the best overall outcome. It’s nice to see a balanced view that doesn’t push medication as a silver bullet.

Gerard Parker

December 1, 2025 AT 22:03When assessing a patient with functional dyspepsia, it’s essential to first verify that the Rome IV criteria are met and that structural causes have been ruled out via endoscopy or appropriate imaging. Once the diagnosis is solidified, the clinician should conduct a brief screening for anxiety and depressive symptoms using validated tools such as the GAD‑7 and PHQ‑9; this not only quantifies comorbid mood disturbances but also informs drug selection. For those with predominant anxiety, an SSRI like escitalopram at 5 mg daily can be initiated, monitoring for nausea and sexual side effects, which are the most common early complaints. In contrast, patients whose chief complaint is early satiety and post‑prandial fullness may benefit more from a low‑dose tricyclic such as amitriptyline 10 mg at bedtime, taking advantage of its anticholinergic slowing of gastric emptying. The dosing strategy should follow a “start low, go slow” paradigm, increasing the dose by 5–10 mg every two weeks if tolerability permits. Follow‑up at four weeks is crucial to assess adverse effects, and a formal symptom reassessment using the Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire should be performed at six to eight weeks; a ≥30 % reduction in score typically justifies continuation. If the patient experiences no meaningful improvement after a 12‑week trial, a switch to a different class-such as an SNRI like venlafaxine, which offers both serotonergic and noradrenergic modulation-may be considered. Throughout the treatment course, clinicians must remain vigilant for red‑flag conditions, including cardiac arrhythmias in patients on TCAs, and avoid prescribing these agents to individuals with significant cardiac disease or a history of bipolar disorder. Tapering the medication after six months of sustained benefit helps prevent withdrawal phenomena, often described as “brain zaps” or rebound dyspepsia. Lastly, integrating adjunctive measures-low‑FODMAP diet, mindfulness‑based stress reduction, and regular aerobic activity-enhances the overall therapeutic effect, addressing both peripheral and central mechanisms of symptom generation.

Scott Davis

December 6, 2025 AT 13:10Good point, tapering is key.

Calvin Smith

December 11, 2025 AT 04:16Oh great, another “miracle pill” for every vague stomach ache – because we all love swapping one drug for another without fixing the root cause.

Brenda Hampton

December 15, 2025 AT 19:23Remember, the best medicine isn’t always a prescription; staying active, eating mindfully, and keeping stress low can dramatically cut down dyspepsia flare‑ups. Small, consistent habits beat occasional pills any day.

Lara A.

December 20, 2025 AT 10:30Don’t be fooled by the glossy charts – big pharma funds the studies that say antidepressants are “safe,” while quietly burying reports of chronic gut dysbiosis and hidden neuro‑toxicity. The truth is being hidden, and we must stay alert.

SandraAnn Clark

December 25, 2025 AT 01:36Life’s mysteries often hide in plain sight; perhaps our bodies whisper answers that we ignore while chasing quick fixes.