Antitrust Issues in Generic Substitution: How Pharma Tactics Block Cheaper Drugs

Jan, 18 2026

Jan, 18 2026

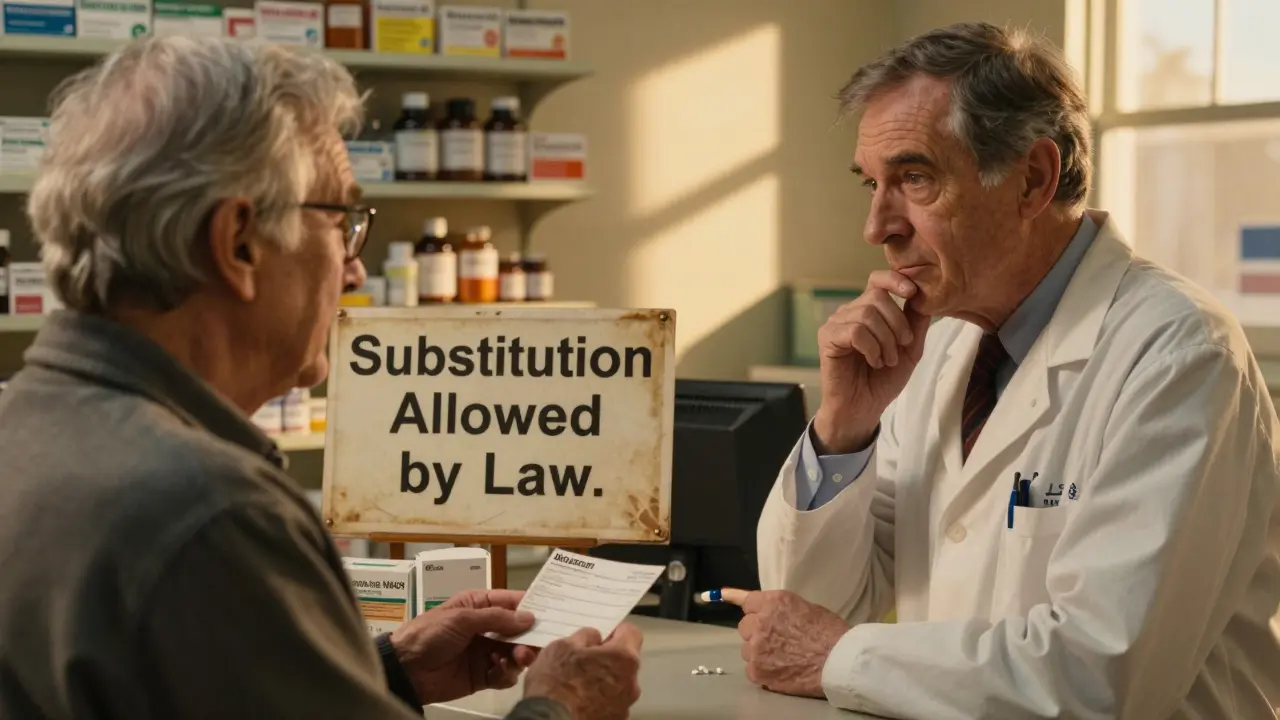

When you fill a prescription for a brand-name drug, you might expect your pharmacist to swap it for a cheaper generic version - especially if your state law allows it. But what if the drugmaker made sure that version no longer exists? That’s not a glitch. It’s a strategy. And it’s breaking the law.

How Generic Substitution Is Supposed to Work

In the U.S., state laws let pharmacists automatically substitute generic drugs for brand-name ones - as long as they’re bioequivalent. This isn’t optional. It’s designed to save money. When a patent expires, generics flood the market. Prices drop by 80% or more. Within months, generics make up 80-90% of sales. That’s how competition is supposed to work. But here’s the catch: brand-name companies don’t want that. Their profits depend on keeping you on their expensive drug. So they’ve found ways to block substitution before generics even hit the shelves.Product Hopping: The Main Antitrust Trick

The most common tactic is called product hopping. It’s simple: when a drug’s patent is about to expire, the maker launches a slightly changed version - maybe a new pill shape, a slow-release formula, or a different delivery method. Then they pull the original drug off the market. Take Namenda. The original version, Namenda IR, was an immediate-release tablet used for Alzheimer’s. When its patent neared expiration, maker Actavis introduced Namenda XR, an extended-release capsule. Thirty days before generics could legally replace Namenda IR, Actavis stopped selling it. Pharmacists couldn’t substitute the generic because the original drug wasn’t available anymore. Patients had to switch to the new version - which was still under patent protection. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals called this out in 2016. They ruled that withdrawing the original drug while launching a minor reformulation was anticompetitive. Why? Because generics can’t compete if the version they’re legally allowed to substitute doesn’t exist. As the court said, this wasn’t innovation - it was a legal loophole.Why Patients Can’t Just Switch Back

You might think: “Why not just go back to the old version?” But it’s not that easy. Once a doctor prescribes the new formulation, they rarely switch back. Patients don’t want to change pills. Pharmacies don’t stock discontinued drugs. Insurance forms often don’t cover the old version anymore. This is called high transaction cost. It’s not about money - it’s about effort. A patient has to schedule another appointment, convince their doctor to change the prescription, and wait for the pharmacy to reorder the old drug. Most people just stick with what’s in front of them. The FTC’s 2022 report confirmed this: product hopping works because it exploits the natural inertia of the healthcare system. It’s not about better medicine. It’s about locking patients in.

Another Tactic: Blocking Generic Access

Even if a generic company wants to make a copy, they need a sample of the original drug to test for bioequivalence. That’s a legal requirement. But some brand-name companies use FDA-mandated safety programs - called REMS - to deny access. REMS are meant to control dangerous drugs. But companies have turned them into weapons. They claim the generic makers can’t safely handle the drug, so they refuse to provide samples. Without samples, generics can’t get FDA approval. A 2017 study by Michael A. Carrier found over 100 generic manufacturers couldn’t get samples for more than 40 drugs. The cost? More than $5 billion a year in lost savings. The FTC called this a textbook case of monopolization. It’s not innovation. It’s obstruction.What Courts Have Said - And Why They’re Split

Not all courts agree on what’s illegal. In 2009, a court dismissed a case against AstraZeneca for switching patients from Prilosec to Nexium. Why? Because Prilosec stayed on the market. The court said adding a new product was fine - even if it was barely different. But in the Namenda case, the court ruled differently. Why? Because Actavis pulled the original drug. The difference? Availability. If the old version still exists, courts tend to see it as competition. If it’s gone, they see it as sabotage. This inconsistency is dangerous. It gives drugmakers a roadmap: withdraw the original, launch a tweaked version, and hope the court doesn’t catch on.Big Cases, Big Penalties

The FTC didn’t just write reports - they took action. In the Namenda case, the FTC got a court order forcing Actavis to keep selling the old version for 30 days after generics launched. That gave patients a real chance to switch. In the Suboxone case, Reckitt Benckiser pulled the tablet version and pushed a film version. They claimed the tablets were unsafe - even though no evidence supported it. The FTC found this was a scare tactic to force patients to switch. They settled for $1.4 billion in 2019 and 2020. Even generic makers aren’t immune. Teva paid a $225 million criminal fine for price-fixing with other generic companies. Glenmark paid $30 million. The DOJ isn’t just going after big brands - they’re cleaning up the whole system.

The Real Cost: Billions Lost

This isn’t theoretical. It’s costing you money. Take Revlimid. When it launched in 2005, it cost $6,000 a month. By 2025, it was $24,000. That’s a 300% increase - and still no generic. Why? Because the company kept filing new patents on minor changes. The same happened with Humira and Keytruda. Together, these three drugs cost U.S. payers an estimated $167 billion more than they would have in Europe, where generic substitution isn’t blocked. Drug Patent Watch estimates that delayed generic entry through product hopping and patent thickets costs Americans over $10 billion a year. That’s money that could’ve gone to insulin, cancer drugs, or mental health care.What’s Changing Now?

The FTC’s 2022 report was a turning point. For the first time, they laid out exactly how product hopping works - and how to stop it. Chair Lina Khan made it clear: this isn’t innovation. It’s exploitation. In 2023, the DOJ and FTC held joint hearings focused on generic competition. Congress is now asking the FTC to recommend new laws. Some states are tightening substitution rules to prevent withdrawal tactics. Others are banning REMS abuse. Legal scholars are pushing for a new standard: if a drug is withdrawn right before generic entry, and the new version offers no real medical benefit, it should be illegal. No more loopholes.What This Means for You

If you take a brand-name drug, ask your pharmacist: “Is there a generic version?” If they say no, ask why. Was the old version pulled? Is the new one really better? Or just more expensive? If you’re on a fixed income, or your insurance has high copays, this isn’t just a policy issue - it’s personal. Every time a company blocks substitution, you pay more. The system was built to save money. But big pharma rewrote the rules. Now, the courts, regulators, and lawmakers are trying to fix it. It’s slow. It’s messy. But it’s happening.What is product hopping in the pharmaceutical industry?

Product hopping is when a drugmaker releases a slightly modified version of a drug - like a new pill form or extended-release formula - just before its patent expires, then pulls the original version off the market. This blocks pharmacists from substituting cheaper generics, keeping patients on the expensive brand-name drug longer.

Why don’t generics just advertise to compete?

Generics can’t compete through advertising because they don’t have the same legal access to patients. State substitution laws are the only cost-efficient way for generics to enter the market. If the original drug is pulled, pharmacists can’t substitute - no matter how much the generic company spends on ads. Courts have recognized this as a structural barrier, not a marketing problem.

Can a brand-name drug company legally withdraw a drug before generics launch?

Technically, yes - companies can discontinue a drug for business reasons. But if they do it right before generics enter, and the new version offers no meaningful medical improvement, courts have ruled it’s anticompetitive. The key is timing and intent. Withdrawing the original drug to block substitution is illegal under antitrust law.

How do REMS programs block generic drug development?

REMS are safety programs meant to control high-risk drugs. But some brand-name companies use them to deny generic manufacturers access to the original drug samples needed for FDA approval. Without samples, generics can’t prove they’re bioequivalent. Over 100 generic companies have reported being blocked this way, costing the system over $5 billion a year in lost savings.

What’s being done to stop these practices?

The FTC has filed lawsuits, won injunctions, and secured billions in settlements. In 2022, they published a major report detailing product hopping tactics. Courts are starting to rule against it, especially when the original drug is withdrawn. Congress and state legislatures are now considering new laws to close loopholes, especially around REMS abuse and timing of drug withdrawals.

How much money do these tactics cost consumers?

An estimated $167 billion has been wasted on just three drugs - Humira, Keytruda, and Revlimid - due to delayed generic entry in the U.S. compared to Europe. Generic substitution can cut drug costs by 80-90%, but product hopping reduces that to 10-20%. That means patients pay thousands more per year for the same treatment.

Christi Steinbeck

January 19, 2026 AT 23:33This is insane. I had to switch my mom from Namenda IR to XR last year and she couldn’t even get the generic because the old one was gone. No one told us why. Now she’s stuck paying $400 a month for a pill that’s basically the same thing. This isn’t healthcare - it’s corporate robbery.

And don’t get me started on REMS. My cousin tried to get a generic for a blood thinner and the brand company refused to send samples. Said it was ‘safety.’ Right. Like they care if we go broke.

sujit paul

January 20, 2026 AT 11:51Dear fellow citizens of the free world: this is not merely corporate malfeasance. This is a calculated assault on the economic sovereignty of the common man. The pharmaceutical industry, in collusion with regulatory capture and judicial ambiguity, has engineered a neo-feudal system wherein the patient is reduced to a passive consumer of artificially inflated commodities. The patent system, once a beacon of innovation, is now a gilded cage. We must awaken. The time for passive acceptance has expired.

Aman Kumar

January 21, 2026 AT 14:32Let’s be brutally honest: this isn’t about patents. It’s about power. These companies don’t just want to make money - they want to control your body’s chemistry. REMS abuse? Product hopping? These aren’t loopholes - they’re weapons. And the FDA, the FTC, the courts? All of them are either complicit or too scared to act. You think this is an accident? No. This is a war. And you’re the battlefield.

And don’t even get me started on how they bribe doctors with ‘educational grants.’

Phil Hillson

January 22, 2026 AT 19:57Okay so like... pharma is bad... got it... but why are we even talking about this like it’s news? Everyone knows the system’s rigged. My cousin’s insulin costs $1200 a month and he works two jobs. This isn’t a scandal - it’s Tuesday.

Also who cares about Namenda? I’ve never heard of it. Can we talk about insulin instead? That’s the real crisis.

Jacob Hill

January 24, 2026 AT 08:39I just want to say thank you for writing this. I’ve been fighting this for years with my insurance company - they keep denying generics because the original drug is ‘no longer available.’ I had to get a lawyer involved just to get my dad’s blood pressure med switched back. It’s exhausting.

And yes - the REMS abuse is real. My brother’s oncology drug? Generic can’t get samples. Four years. Four years. And they’re still charging $15,000 a dose.

We need to push for state-level bans on withdrawal tactics. Now.

Lewis Yeaple

January 24, 2026 AT 18:29While the article presents a compelling narrative regarding anticompetitive behavior in the pharmaceutical sector, it is imperative to acknowledge the legal distinctions between product differentiation and market withdrawal. The judicial inconsistency noted - particularly between the AstraZeneca and Actavis rulings - underscores the necessity for legislative codification of clear, objective criteria to define anticompetitive conduct. Absent such clarity, regulatory overreach risks chilling legitimate innovation.

Furthermore, the economic impact estimates cited, while alarming, require methodological scrutiny. Are they controlling for inflation, R&D expenditures, and global pricing differentials? Without this, the $167 billion figure may be misleading.

Jake Rudin

January 25, 2026 AT 13:26What’s really being hidden here isn’t just the money - it’s the silence. The patients who don’t know they’re being manipulated. The pharmacists who are told ‘we don’t stock that anymore’ and just shrug. The doctors who don’t question the switch because they’re too busy.

This isn’t a conspiracy. It’s a system that rewards inertia. And the most dangerous part? It’s legal. Not because it’s right - but because the law hasn’t caught up to the manipulation.

We’ve built a world where innovation means making a pill that’s slightly harder to swallow - so you can’t switch to the cheaper one. That’s not progress. That’s psychological warfare.

And we’re all just… waiting for someone else to fix it.

Astha Jain

January 26, 2026 AT 19:20OMG like i just realized... i’ve been paying for brand name drugs for years and i thought it was because my doc 'recommended' them... but what if they were just the only ones left?? like... what if the generic was there but the original got yanked??

also why is everyone so calm about this?? its literally stealing from sick people. like... i know im not a doctor but this feels so wrong. also i think the word is 'REMS' not 'remes' lol

Valerie DeLoach

January 27, 2026 AT 16:43This is why I teach health policy to undergrads. This isn’t just about drugs - it’s about trust. We built a system where patients, pharmacists, and doctors were supposed to work together to lower costs. Now, the system is rigged to make everyone feel powerless.

But here’s the thing: awareness is power. When you ask your pharmacist, ‘Is there a generic?’ - you’re not just saving money. You’re challenging the narrative. You’re saying, ‘I see what you’re doing.’

And that’s how change starts. Not in courtrooms - in conversations. Keep asking. Keep pushing. You’re not alone.

Tracy Howard

January 28, 2026 AT 12:54Can we just admit that American pharma is the most corrupt industry on Earth? They’ve turned healthcare into a casino where the house always wins - and the players are dying. Canada doesn’t do this. The UK doesn’t do this. Even Germany has better rules. But here? We let them pull the rug out from under sick people and call it ‘innovation.’

It’s not capitalism. It’s capitalism with a chokehold. And until we treat Big Pharma like the cartel it is - nothing changes. We need national price controls. Now.

Lydia H.

January 29, 2026 AT 22:08I’ve been on a brand-name med for 7 years. My pharmacist finally told me last month that the generic was available - but only because the brand company got sued and had to bring back the old version. I cried. Not because I was happy. Because I realized I’d been paying $300 a month for nothing.

And honestly? I’m mad I didn’t ask sooner. We’re all just trying to survive. But this? This is the kind of thing that breaks people. Slowly. Quietly. And nobody notices until it’s too late.